Clark County residents lost $1.9 million via “legalized theft” last year, new study shows

Executive Summary

Today, the Nevada Policy Research Institute released the first-ever geographical analysis of how the controversial civil asset forfeiture program is used by the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD).

Civil asset forfeiture is a practice whereby law enforcement officials can seize property they suspect may be connected to a crime. In certain cases, that property can be forfeited without even criminal charges being filed.

Historically, the public was not provided with any information as to how this program was being used. But recently passed legislation now requires that all Nevada law enforcement agencies file annual reports with the Attorney General regarding their seizures and forfeitures.

For the fiscal year ending 2016, Metro reported total seizures of more than $2.1 million and total forfeitures of over $1.9 million worth of cash and property.

In Who Does Civil Asset Forfeiture Target Most?, NPRI policy analyst Daniel Honchariw analyzed this data and found that most forfeitures were for amounts less than $1,000 — making it cost-prohibitive for innocent parties to contest the seizure, as the legal fees in doing so would almost certainly surpass the value of the seized property.

Honchariw considers such practices a form of government theft.

“The most troubling aspect of this practice is that the seizing law enforcement agency directly profits from the forfeitures. And in the vast majority of cases the value of the property seized is less than the likely legal fees needed to contest the seizure, making the whole process nothing more than a form of legalized theft — with the government as the perpetrator.”

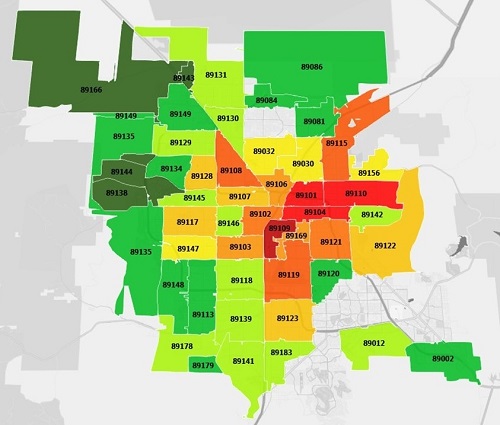

Honchariw’s first of its kind analysis also uncovered where forfeitures occur by combining the data reported to the AG alongside several hundred individual crime reports obtained via a series of public records requests. The data show that forfeitures occurred mostly in low-income, minority neighborhoods.

“In addition to the ethical problems raised by the practice, there should be concerns over whether or not this is the most efficient use of Metro’s resources. In many cases Metro’s related processing and storage costs far outweigh the value of the seized assets,” explained Honchariw.

Low-dollar assets were not a rare occurrence in 2016, according to the report. There were 43 forfeiture cases involving assets worth $100 or less — with one case conducted over a paltry 74 cents!

The report concludes by recommending that the practice be abolished completely, as law enforcement seeking the forfeiture of assets related to criminal acts can do so under criminal laws, which provide for due process.

In lieu of that, Honchariw points to New Mexico’s recent reforms as an ideal model for Nevada to follow, which eliminate the profit-incentive by directing the proceeds of all forfeited assets to the state or county general fund, while restoring due process to innocent property owners.

The full report can be viewed here.

For more information or to schedule an interview with report author Daniel Honchariw, please contact Michael Schaus at 702.222.0642 or MS@NPRI.ORG.