Solution of the week: The many problems of the margin tax

Editor's note: Earlier this year, NPRI released Solutions 2013, a comprehensive sourcebook of research and recommendations in 39 policy areas. Now, each week during the run-up to the 2013 Legislative Session, NPRI will highlight one of these as its Solution of the Week. If you would like NPRI to speak to your organization about this or another policy recommendation, please contact Victor Joecks at vj@npri.org. Solutions 2013 is also available online here.

In 2011, some lawmakers proposed a new tax instrument to be levied against Nevada businesses. This proposed business margin tax — modeled after a Texas tax instrument of the same name — would be assessed against firms with total taxable-year revenue exceeding $1,000,000. For these firms, the proposed tax rate of 0.8 percent would be assessed against the least of:

A) 70 percent of total revenue,

B) Total revenue minus wages, or

C) Total revenue minus the cost of goods sold

Proponents said the margin tax was intended to eventually replace Nevada's tax on private‐sector payroll, the Modified Business Tax. However, while repeal of the MBT should be considered, the margin-tax proposal is an inferior alternative.

Key Points

The business margin tax is a hybrid, combining negative features of both corporate‐income and gross‐receipts taxes. According to the Tax Foundation, "the Texas ‘margin' tax is really a badly designed corporate income tax." One difference, however, is that the margin tax would create a tax liability even for businesses that operate at a financial loss — meaning the tax also possesses the negative attributes of gross-receipts taxation.

Corporate-income taxes exacerbate revenue volatility. Numerous analyses, including those of the Tax Foundation and NPRI, have shown that state corporate-income-tax revenues are extremely volatile and would be far more volatile than any tax instrument currently employed in Nevada. This volatility renders financial planning more difficult, particularly in states like Nevada that craft biennial budgets.

Gross‐receipts taxes are "distortive and destructive." The Tax Foundation calls gross‐receipts taxation "distortive and destructive," because such taxes "pyramid" as they are assessed at every level of production. Thus, highly complex goods that require multiple stages of production are repeatedly subjected to the tax. This results in a higher effective tax rate on more complex goods, which distorts economic behavior and would retard Nevada's economic diversification. As the Tax Foundation says, "Gross receipts taxes do not belong in any program of tax reform."

A margin tax imposes high compliance costs. Margin taxes are extremely complicated — a complication compounded by the vague legal definitions of terms such as "cost of goods sold." Consequently, high compliance costs accompany margin taxes, imposing disproportionate burdens on small businesses, which lack the accounting expertise to navigate the tax.

The Texas margin tax is rife with problems. In 2009, Texas lawmakers heard over 100 bills to modify or repeal that state's margin tax — at the time only three years old. The tax has consistently underperformed revenue projections and is widely perceived as unfair to small or struggling businesses.

Recommendations

Reject any proposal for a Texas‐style margin tax. Tax scholar John L. Mikesell has appropriately referred to the margin tax as a "badly designed business profits tax … combin[ing] all the problems of minimum income taxation in general — excess compliance and administrative cost, penalization of the unsuccessful business, undesirable incentive impacts, doubtful equity basis — with those of taxation according to gross receipts."

The Tax Foundation also declares, "there is no sensible case for gross receipts taxation, or modified gross receipts taxes such as a Texas‐style margin tax." Indeed, there is broad consensus among tax economists that gross receipts or margin taxes are more destructive than alternative tax instruments yielding the same amount of revenue. As such, Nevada lawmakers should never consider the imposition of a margin tax in the Silver State.

____________________________________________

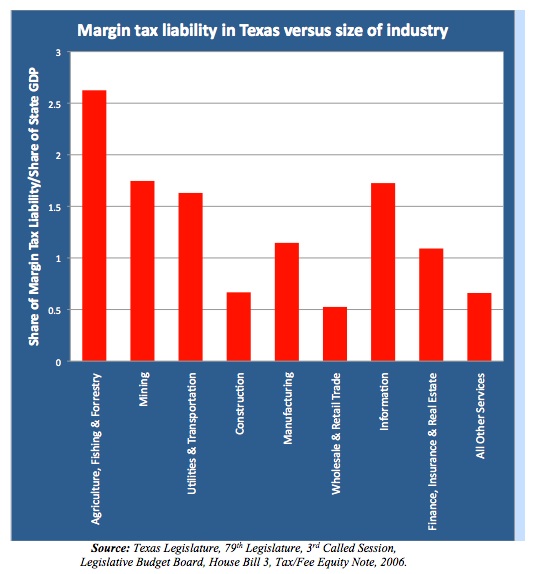

Texas margin tax creates inequitable tax liability. The margin tax allows industries that are either heavily labor‐intensive or heavily capital‐intensive to declare higher exemptions. Industries that employ relatively similar levels of labor and capital are unable to declare higher exemptions and face a larger tax liability. As a result, some industries face a tax liability disproportionate to their share of the state economy. The share of margin-tax revenues paid by Texas' agriculture industry, for instance, is 2.6 times greater than its share of economic output.

Geoffrey Lawrence is deputy policy director at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org.

Read more: