Clark County Government Unions: When Being in the Top 1 Percent Just isn’t Enough

Executive Summary

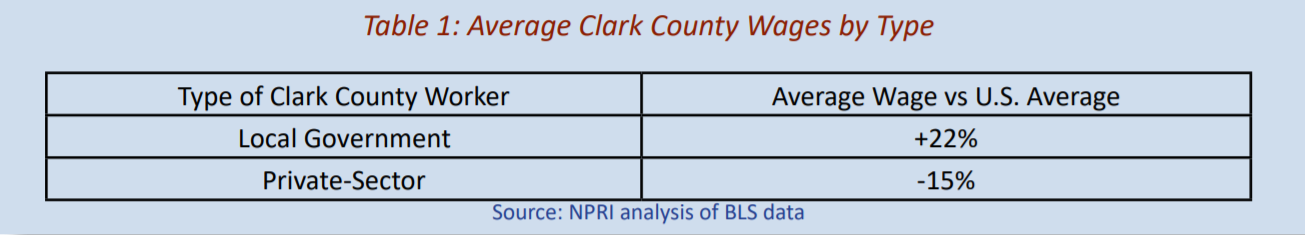

- The average wage received by Clark County’s local government workers was greater than the amount received by their public-sector peers in over 99 percent of counties nationwide, according to the most recent data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Clark County workers also enjoy richer retirement and health benefits and nearly twice as many paid holidays and sick days than comparable private-sector workers, in addition to more favorable policies that allow for “banking” of unused sick leave to be cashed in at a later data.

- Despite the above, the union representing Clark County workers — SEIU of Nevada — recently rejected an offer for an across-the-board raise of at least 2 percent next year, and is demanding 3.25 percent instead.

In the 2017 third quarter, local government workers in Clark County received an average weekly wage of $1,155 — which ranked 55th out of the 2,867 counties surveyed nationwide, and was about 22 percent higher than the national average of $943 for local government workers.[i]

Of the few dozen counties with higher local government wages than Clark County, almost all are in states with much higher costs of living, including California, New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts.

When the average wages are adjusted to reflect the different price levels faced by the average consumer in each state, as calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ Regional Price Parities 2015 report, Clark County jumps to number 25 on the list — placing its employees firmly within the top 1 percent of counties with the highest paid local government workers nationwide.

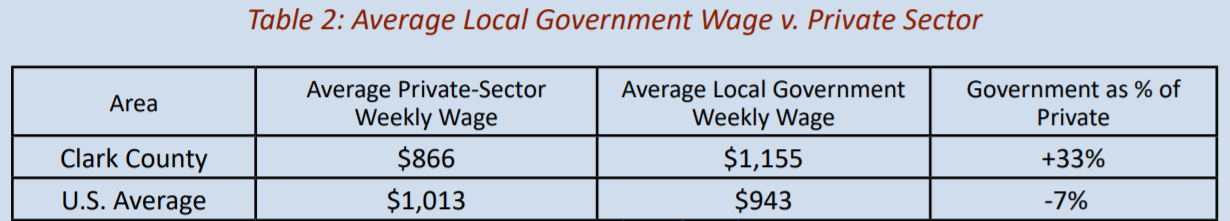

Clark County private-sector workers, by comparison, earned an average weekly wage of $866, which was about 15 percent less than the national average of $1,013.

Clark County local government wages are also atypically large when measured as a percentage of private-sector earnings.

Nationally, the average local government weekly wage of $943 was about 7 percent less than the private-sector average of $1,013. But in Clark County, local government workers received an average wage that was 33 percent more than the amount received by Clark County private-sector workers:

Why it matters

Because employee compensation is by far the single largest category of government expenditures — accounting for roughly 65 percent of Clark County’s general fund and over 80 percent of Las Vegas’ and Henderson’s operating fund — it is critical that taxpayers have complete and accurate information regarding the government pay packages that they are required to fund.

In addition to wages, compensation also includes employer-paid retirement and health benefits, paid leave, job security and retiree health benefits.

While the BLS data is for all local government workers within Clark County, and not merely those who work directly for the county itself, it is nonetheless a very strong indication that wages for county workers are already at very competitive levels.

Because each collective bargaining group can receive slightly different benefits, this analysis will be limited to only the benefits provided to SEIU-represented, non-supervisory (aka rank-and-file) workers employed by either Clark County, the Clark County Law Library, the Clark County Regional Flood Control District or the Clark County Water Reclamation District.

For simplicity, this bargaining group will be described as “Clark County government workers” going forward.

Retirement and Health Benefits

Clark County government workers receive employer-paid retirement benefits that cost nearly 6 times more than the 5 percent of pay that the average private employer spends on their employees’ retirement benefits.[ii]

In terms of value of the benefit ultimately provided, all Nevada government workers belong to the state pension fund, which provides retirement benefits that are at least 55 percent richer than what a comparable private-sector worker will receive.[iii]

For health insurance, all Clark County workers hired after April 19, 2011 pay 10 percent of the premium for group medical and dental insurance, regardless of plan type.

The average regional private-sector worker, by contrast, pays 22 percent of the premium for single coverage health insurance and 35 percent for family coverage.[iv]

Paid Leave

Clark County workers also receive generous sick and vacation leave policies that surpass what most private-sector workers receive. For example, all Clark County workers receive at least 12 paid holiday days a year, including their birthday, which is nearly twice as many as the 7 paid holiday days received by the average private-sector worker.

Additionally, Clark County employees who have been employed for ten years or longer receive 15 days of paid sick leave annually, which is nearly twice as much as the 8 days received, on average, by comparable private-sector workers.

Table 3: Private Sector Benefits v. Clark County Government Benefits

Type of Compensation |

Private Sector |

Clark County Government |

Clark County vs Private |

Employer-Paid Retirement, as a Percent of Pay |

5% |

28% |

+460% |

Employer-Paid Share of Family Medical Premium |

65% |

90% |

N/A |

Paid Holidays |

7 |

12 |

+71% |

Annual Paid Sick Leave for 10+ year employees |

8 |

15 |

+87.5% |

Annual Paid Vacation Leave for 10+ year employees |

17 |

18 |

+6% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017 National Compensation Survey; SEIU’s governing Collective Bargaining Agreement

And while 90 percent of private employers impose a limit on the number of unused sick days that can be rolled over, no such limit exists for Clark County workers, enabling some high-ranking officials to cash in over $200,000 worth of unused leave before retirement.

The only aspect of Clark County government workers’ compensation that did not significantly exceed average private-sector levels was the amount of paid vacation days, which are roughly equal to what the average private-sector worker receives.

Finally, like all government workers, Clark County workers receive vastly higher levels of job security than the average taxpayer receives, which has been estimated to be worth approximately 8 percent of wages.[v]

The cause

As NPRI has long reported, such outsized pay packages for Nevada’s local government workers — and the burden they impose on the taxpayers who, on average, earn much less themselves — are the inevitable result of the state’s mandatory collective bargaining laws.

Because Nevada state law forces local governments to bargain with a single government union, the union is able to wield this monopoly power to push labor costs well above market prices — a cost that is then passed on to captive taxpayers.

Adding insult to injury is the fact that these negotiations are done entirely in secret — ensuring that the taxpaying public is shut out of the process entirely.

Unsurprisingly, this arrangement has resulted in about $1 billion annually in added costs to Nevada taxpayers, according to the most comprehensive study ever conducted on this issue by former NPRI Policy Director Geoffrey Lawrence and scholars at the Heritage Foundation.

The current landscape is a result of the profound differences between unionization in the public and private sectors — which is why, historically, the idea of government unions was widely opposed by economists, policymakers and politicians on all sides of the ideological debate.

In addition to well documented opposition from traditionally pro-union policymakers such as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, even labor unions themselves historically opposed the concept of unionizing government workers.

For example, in 1955, AFL-CIO President George Meany said, “It is impossible to bargain collectively with the government.” Four years later, the AFL-CIO executive council passed a resolution declaring that, “In terms of accepted collective bargaining procedures, government workers have no right beyond the authority to petition Congress — a right available to every citizen.”[vi]

So what changed?

As Geoffrey Lawrence and Cameron Belt document in The Rise of Government Unions: A review of public-sector unions and their impact on public policy, the shift towards favoring government unions didn’t occur because of any change in logic or analysis, but was simply the result of union bosses scrambling to find new dues-paying members in response to declining private-sector membership:

The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) was the first labor organization to explicitly acknowledge these points and to begin a systematic effort to bring compulsory collective bargaining to state and local governments. “Industrial unions seem to be at the end of a line…as more and more plants are automated,” and craft union membership “is growing only slowly,” the organization observed. “In public employment, however, there is an expanding reservoir of workers.”

While the original labor movement was created to prevent the exploitation of workers by profit-hungry corporations, no such justification exists for unionization in the public sector, which has neither owners nor profits over which to negotiate.

And because the government is funded via taxation, it faces none of the cost restraints found in the for-profit private sector. Private employers, on the other hand, are only able to generate revenue to the extent that consumers voluntarily purchase their goods or services.

Governments, by contrast, can finance above-market compensation by simply taxing the public. Most problematic is that the elected officials who approve these labor contracts bear none of the cost. In fact, these elected officials are routinely rewarded for doing so, as the concentrated political support bestowed upon them by appreciative government unions far outweighs the cost of taxpayers’ dispersed frustration.

On this point, Lawrence and Belt observe that:

Instead of resisting union demands, politician-employers have a keen interest in encouraging unionization among government employees because they can use government unions as political machines to secure election.

Thus, mandatory collective bargaining in the public sector has led to the very one-sided, exploitative arrangement that private-sector unions were originally designed to prevent — albeit with organized labor wielding the power, and the taxpaying public at large left largely powerless.

Such an uneven power dynamic has been fully exploited by Nevada’s local government unions, who need not be constrained to simply advocate for fair, market-based wages, but instead have successfully lobbied for substantially inflated compensation packages — all at taxpayer expense.

Lawrence and Belt recount a particularly egregious example from North Las Vegas, where government unions used their political muscle to successfully further their own interests, at the expense of the community at large:

Leading up to the 2011 city council election city police and fire unions lobbied for higher city property taxes to sustain their well above-average compensation packages. This happened after a steering committee formed to help the city avert bankruptcy advised that it would be “very unfair to saddle the public, struggling right now, with fee or tax increases to sustain salaries that are double, triple what their household incomes are.”

In fact, public records indicate that only 10 percent of the city’s firefighters and 25 percent of the city’s police force actually lived within city limits, so the unions were asking the city council to levy taxes that most members would not pay. Union operatives went so far as to erect signs around the city warning “We can no longer guarantee your safety,” in an effort to secure community acquiescence to the tax proposal.

But the union still faced a problem: Councilman Richard Cherchio was disinclined to raise city property taxes and instead demanded the unions make concessions in their collective bargaining agreements or face layoffs. Union officials responded by circulating fliers that made false claims about Cherchio’s record as a councilman, including that he had caused the city’s crime rate to spike 50 percent.

Union officials also flouted state election laws: exceeding donation limits to Cherchio’s union-backed opponent and failing to file financial disclosure reports on time. Cherchio’s opponent, Wade Wagner, welcomed the union support — in addition to the on-the-ground support, more than half of Wagner’s campaign contributions came from union sources. In the end, the unions prevailed and Wagner won the election by a single vote.

Sadly, such intimidation tactics appear frequently. In researching the legislative history behind the Nevada Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS), NPRI learned that:

A lawmaker received numerous threatening phone calls and emails from Las Vegas police officers after he suggested a slightly less generous pension enhancement than the one demanded by unions — one of the most shocking findings from a historical analysis documenting how the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Nevada (PERS) grew to become the nation’s richest public pension plan.

“The fact that a lawmaker received threats after proposing an enhancement, albeit one not as rich as demanded, demonstrates how pervasive this culture of union entitlement has become,” said Robert Fellner, director of transparency research at the Nevada Policy Research Institute.

The union’s preferred enhancement ultimately passed, paving the way for one 38-year old to draw an annual $110,804 pension, while working full-time. Given the individual’s age, actuaries project he will receive a total of over $13 million in combined lifetime PERS payouts.

In 2011, Clark County Commissioner Steve Sisolak received death threats as a result of trying to combat sick leave abuses at the fire station, as reported by the Las Vegas Sun in “Sisolak calls for investigation of firefighter sick leave”:

In 2009, Clark County Commissioner Steve Sisolak began looking hard at Fire Department costs. He had received a deluge of angry calls and e-mails from constituents wondering why the unionized firefighters weren’t accepting salary or benefits reductions as the county dealt with budget cuts and the local economy continued its slide.

“Everybody was losing their jobs, their homes,” Sisolak said.

For much of that year, he was the only commissioner willing to criticize their salaries, benefits and retirement packages that averaged about $180,000 in 2009.

In retaliation, members of the union showed up at Sisolak’s public meetings to glare at him. He said he received death threats, which prompted county administrators to post park police at commission meetings. A city firefighter posted on Facebook that she’d like to shoot him.[vii]

Nevada’s distinct treatment of state and local government workers

While Nevada bestows the most powerful advantages possible upon local government unions, it outlaws collective bargaining entirely for state government workers.

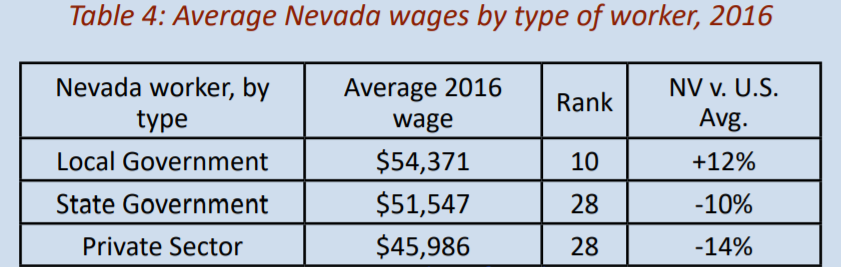

Thus, the ability for local government unions to drive their wages far above market levels can be easily seen by comparing how their wages rank against local government workers nationwide, and measuring that metric against how Nevada’s state government workers fare against their peers nationwide:

Nevada’s state government workers’ average wage of $51,547 ranked 28th when compared to the average wage received by state government workers nationwide. This is identical to the ranking for Nevada’s average private-sector wage, which seems appropriate.

The average wage for Nevada’s local government workers, however, ranked significantly higher at 10th highest nationwide.

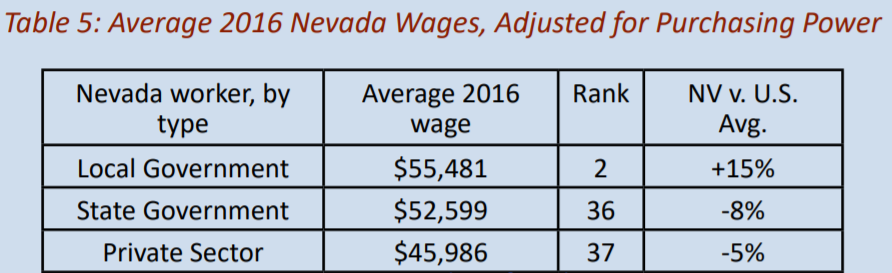

This disparity is magnified once regional purchasing power is accounted for, which boosts Nevada local government workers’ average wage to the 2nd highest nationwide, while Nevada’s private workers rank 37th:

When compared to local government workers nationwide, the average wage for Nevada’s local government workers is 15 percent above the national average and ranks 2nd highest nationwide. Nevada’s private-sector workers, however, earn 5 percent less than the average wage received by private-sector workers nationally.

Once again, it is important to note that state government workers — which lack the coercive, monopolistic powers granted to Nevada’s local government employees — are roughly on par with Nevada’s private sector.

It is thus reasonable to conclude that the significantly above-average compensation received by Nevada’s local government workers reflect the undue influence of their government unions, as opposed to what is merely necessary to attract and retain a qualified workforce.

What the union wants is simple: More.

In light of the above, it would be entirely reasonable for Clark County to implement a pay freeze next year in an effort to bring compensation back down to market levels.

However, that’s not what’s happening.

In reality, Clark County offered a 2 percent across-the-board pay raise to all of its employees.[viii]

One still laboring under the delusion that government unions are simply out to secure “fair” wages for their members might have expected SEIU to have sheepishly accepted the offer as a welcome gift. After all, while a pay freeze would have been understandable given their already-inflated wages, it would be nonetheless foolish to expect the union to turn down a possible raise for its members.

Far from accepting a modest raise, however, the SEIU responded in the only manner it knows how, and precisely as it should, given the lopsided amount of power the Nevada Legislature has bestowed upon it: It demanded even more.

Despite representing a workforce that receives an average wage higher than local government employees in 99 percent of counties nationwide, SEIU of Nevada rejected an offer for an across-the-board raise of at least 2 percent next year, and is instead demanding 3.25 percent.[ix]

Frankly, it’s a shrewd move by the union, given there’s a current gubernatorial primary race between Steve Sisolak and Chris Giunchigliani — both of whom need the union’s support to prevail.

And that, after all, is the logical and necessary outcome of unionization in government — which is why those advocating for the public interest went to great lengths to warn that, “the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service.”[x]

Should the Nevada Legislature ever choose to repeal Right to Work and/or impose collective bargaining for state government workers, the added costs could very well break the state. While states like California have the tax base to support such inflated state-level compensation — for the time being, anyway — Nevada has no such pot of gold.

Of course, the bankrupting of Nevada will not happen overnight.

Instead, hardworking Nevadans will see their incomes steadily eroded by higher taxes and fees — all the while receiving less public services in return for their increased tax burden.

To ensure all Nevadans have a chance to prosper, lawmakers should extend the prohibition of government unions from the state level to also include local government workers. Absent that, lawmakers could provide much-needed relief to Nevadans and increased economic growth by simply removing the power of compulsion currently enjoyed by local government unions, making collective bargaining optional, instead of mandatory.

Should lawmakers choose to go in the other direction, Nevada’s future may very well end up resembling the ruin currently playing out in present-day Illinois, where citizens are fleeing for lower-tax jurisdictions[xi], while the state is scrambling to cover its inflated costs with record-high tax hikes.[xii]