Solution of the week: NSHE finance

Editor's note: Earlier this year, NPRI released Solutions 2013, a comprehensive sourcebook of research and recommendations in 39 policy areas. Now, each week during the run-up to the 2013 Legislative Session, NPRI is highlighting one of these as its Solution of the Week. If you would like NPRI to speak to your organization about this or another policy recommendation, please contact Victor Joecks at vj@npri.org. Solutions 2013 is also available online here.

State financial support for the Nevada System of Higher Education (NSHE) has grown from $431 million in FY 2000 to $798 million in FY 2010. Over the same period, the number of full‐time equivalent students served by NSHE has grown from 48,688 to 69,154. This means that state support for each full‐time student grew from $8,852 in FY 2000 to $11,568 in FY 2010 — an increase of 30.7 percent.

State support includes in‐state tuition charges which are funneled through the general fund and then reallocated back to NSHE institutions. In addition, NSHE institutions receive a significant amount of self‐supported funds. In FY 2000, these totaled $402 million and, by FY 2010, they totaled $924 million. This brought total spending in each of these years to $833 million and $1.724 billion, respectively — or $17,106 and $24,936 per full‐time student. Yet, the share of these costs borne directly by students is remarkably low when NSHE institutions are compared to public universities around the nation.

Key Points

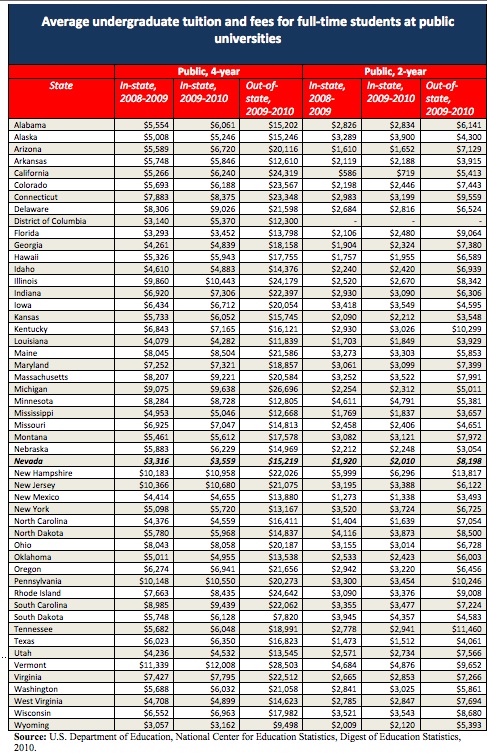

Nevadans face some of the lowest in‐state tuition rates in the nation. According to the U.S. Department of Education, the average cost of in‐state tuition and fees to attend a four‐year, public university in Nevada was $3,559 for the 2009‐10 school year. That amount was the third lowest in the nation, $2,649 below the national median.

Use of general‐fund dollars for NSHE is regressive. Studies show that children of more affluent families are far more likely to attend college than children of low-income families. Yet, state taxes in Nevada are paid by individuals at every point on the income scale. Therefore, general‐fund spending on NSHE tends to have a statistically regressive impact, transferring resources from the less to the more wealthy.

NSHE fails the majority of its students. Among students who enroll as first‐time college freshmen at the University of Nevada, Reno, only 46.3 percent graduate within six years. At the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, the rate is even lower — at 39.4 percent. At both universities, the four‐year graduation rate is a meager 12 percent.

Subsidized tuition rates discourage private competition. The high degree of subsidization for NSHE institutions impairs the ability of high‐quality private universities to come to Nevada and compete for students. This absence of competition, in turn, allows NSHE's poor performance to continue, unchecked.

Many of the nation's most successful public universities — from the University of California, Berkeley to Penn. State University — achieved prominence as a result of competing directly with major private universities nearby. Not coincidentally, these top‐ranked public universities also charge tuition rates that are less dramatically subsidized than those found in Nevada.

Recommendations

Fund students, not institutions. Instead of subsidizing a failing state monopoly on higher education, lawmakers should harness the power of markets to raise the quality of Nevada's higher education marketplace. This can be done by determining a value of state support to be guaranteed each full‐time student and then allocating funds to institutions in accord with their in‐state student enrollment.

Any university in Nevada whose quality attracts students — whether an NSHE institution or not — should be eligible to receive this support. Over time, this will allow top‐notch private universities to develop within the state, bringing the competition in the higher‐education marketplace that Nevada desperately needs.

Allow regents to set and keep tuition rates. The combination of tuition and per‐pupil state support attracted by each institution should remain with the institution itself and not pass through the state general fund.

Geoffrey Lawrence is deputy policy director at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more visit http://npri.org.

Read more: