All parties agree: dual-serving legislators are bad for democracy

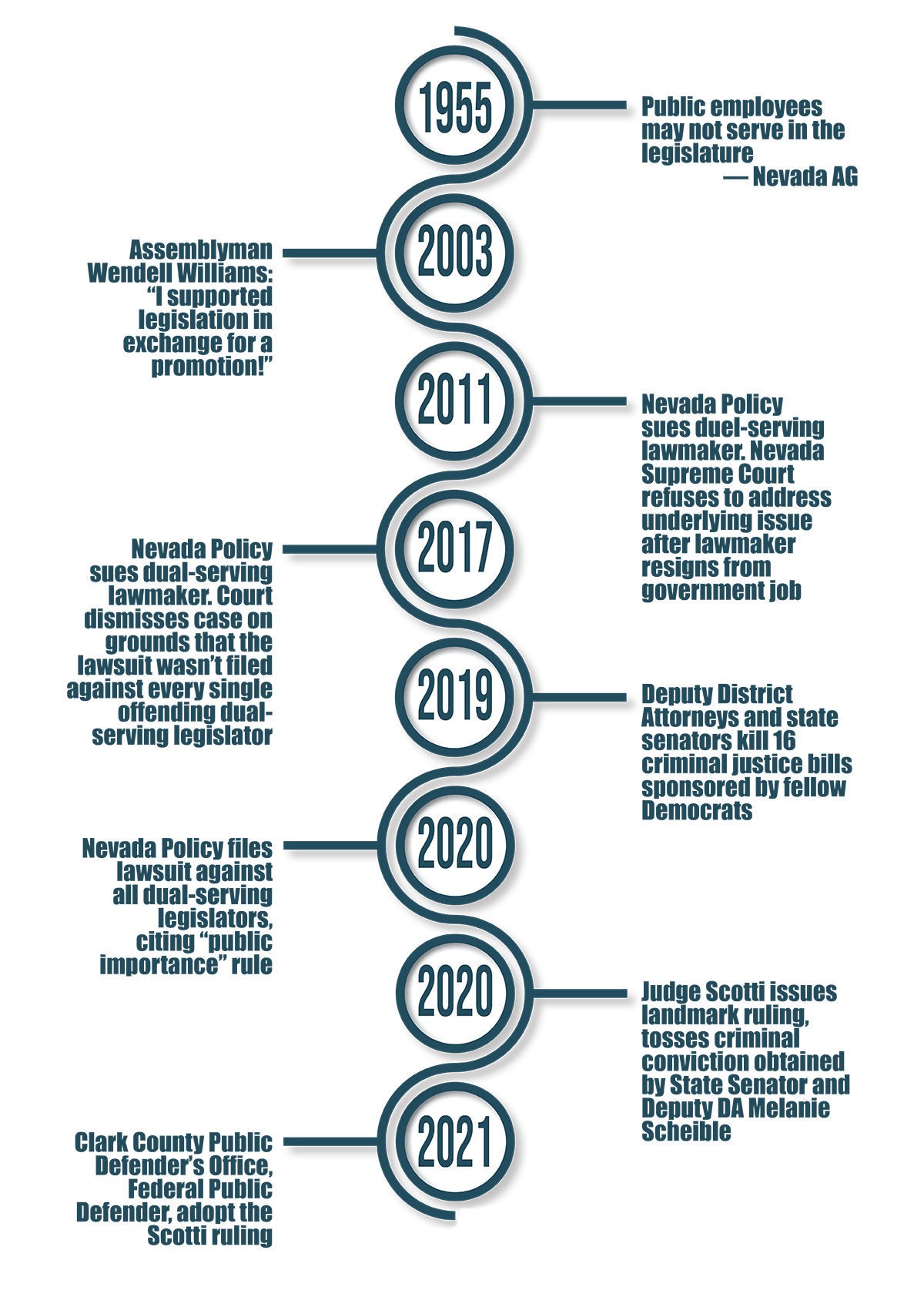

In 1951, the Nevada Attorney General issued the first of several official advisory opinions addressing whether legislators can simultaneously serve in other areas of government. The opinions were short and to the point, much like the text of Nevada’s constitutional separation of powers clause: because legislators are prohibited from exercising “any functions” related to any other branch of government, they therefore cannot simultaneously be employed by a state or local government agency.

But because those opinions did not have the force of law, and because government never restrains itself, the prohibited practice of dual-serving legislators continued unabated.

Today, there are nine government employees simultaneously serving as state legislators, which includes the leaders of both the Assembly and Senate. Having the Legislature run by government employees threatens the very notion of a representative government. Where, exactly, do the people exercise their power if even the Legislature is controlled by government?

In their willingness to disregard such a foundational principle of our representative system of government, the offending dual-serving legislators are, in effect, sending Nevadans the following message:

Yes, you’ve identified a constitutional rule forbidding us from serving in two branches of government simultaneously… Now let’s see you try and enforce it.

That time has finally arrived.

The spark was a landmark ruling issued last year by former Clark County Judge Richard Scotti, who threw out a criminal conviction obtained by Clark County prosecutor and state senator Melanie Scheible. Nevada’s separation of powers doctrine, Judge Scotti explained, means that “an individual may not serve simultaneously as the law-maker and the law-enforcer of the laws of the State of Nevada.” Consequently, Scheible’s unconstitutional actions meant she “did not have the legal authority to prosecute,” rendering the trial “a nullity.”

The Scotti ruling has since been appealed to the Nevada Supreme Court. And while it is possible that the Court might overturn that ruling on procedural grounds, that will not be the end of the matter. That’s because the Scotti ruling has now been adopted as the de facto official position of the Clark County Public Defender’s Office — which has indicated it intends to raise this challenge in numerous other cases. And they are not alone. The Federal Public Defender for the District of Nevada is also arguing for enforcement of Nevada’s separation of powers doctrine, as articulated by the Judge Scotti ruling, in a just-filed motion in yet another case.

The enforcement of Nevada’s constitutional separation of powers provision has evaded judicial review for so long because of so-called “standing” rules that made it all but impossible for taxpayers to bring constitutional challenges on their own. The adoption of the Scotti ruling by the public defender’s office, however, solves that problem.

In other words, the floodgates are now open, and a definitive ruling from the Nevada Supreme Court is now all but assured. While these challenges are somewhat narrow in scope — and only address the unconstitutionality of legislators acting as prosecutors — the Nevada Policy lawsuit seeks judicial enforcement of the separation of powers doctrine against all dual-serving legislators.

Why it matters

With a resolution finally on the horizon, it’s worth revisiting why prohibiting dual-serving legislators is so important.

The first reason is straightforward: The constitution forbids it, and constitutional limits shouldn’t be ignored simply because those subject to its restraints would prefer it that way. Indeed, faithful adherence to constitutional limits is a requirement for any government that claims to serve the people, rather than merely ruling over them.

The second reason is more practical: permitting government employees to serve as legislators leads to a Legislature that increasingly serves the needs of government, rather than the people.

It is important to remember what makes government so profoundly different from private-sector employers — only government can claim the legitimate use of force and coercion, most notably through taxation. That the people retain ultimate authority over this coercive power, through their elected representatives in the Legislature, is the only thing that makes such coercion ostensibly tolerable to a free society.

As the beneficiaries of taxation themselves, there is an omnipresent and unavoidable conflict inherent to having government employees serve in the Legislature. Is the dual-serving legislator supporting higher taxes because it is in the best interest of Nevadans or because it serves the needs of their employer?

This inseparable conflict means that every dual-serving legislator dilutes the Legislature’s ability to act on behalf of the people. In this way, dual service not only violates Nevada’s constitutional separation of powers doctrine; it also undermines the very foundation of our system of representative government.

All parties agree: there is an obvious conflict here

Few have done more to highlight the problems with dual-serving legislators than former Assemblyman and Las Vegas administrator Wendell Williams. No one seriously disputed that the city hired Williams because of his influence as a state legislator. Williams even admitted as much during a 2003 council meeting, where he relayed how city officials relied on him to open doors for them in a way that regular lobbyists simply could not.

Indeed, no one seemed able to explain what Williams actually did for the city other than lobbying (as a member of the legislature himself). Even Williams described his duties and responsibilities in terms of lobbying, rather than whatever it was an “administrative officer” in the city’s Neighborhood Services department was supposed to do:

“I was given assignments to work on in the Legislature,” Williams testified when describing what he did after being transferred to the city’s Neighborhood Services department. As an example, Williams cited his role in helping to develop the city’s new childcare initiative, after which he then “went to the legislature…and got the funding for it,” according to his sworn testimony.

That there is a benefit for governments to hire legislators for their superlobbyist abilities is undeniable. Recalling her time as an assistant city manager, former Las Vegas councilwoman Lynette Boggs McDonald explained how it was an unspoken policy to try and get as many legislators on the government payroll as possible:

“I can tell you that, back in the early 90s there was a desire to have members of the Legislature working for the City of Las Vegas because it was somewhat of a wink and a nod at…that understanding that they had that ‘value’ to the City of Las Vegas.”

To get a sense of how valuable having legislators on the payroll is to government agencies, consider the sheer breadth of scandals and misconduct that Las Vegas was comfortable overlooking to keep Williams on the payroll: campaign finance violations, reckless driving citations, a warrant issued for failing to pay those citations, racking up huge charges on the city’s phone bill for personal calls, barely ever showing up to work and submitting falsified timecards to collect thousands of taxpayer dollars for work never performed.

So, you can imagine the city’s surprise when, after tolerating all of that, Williams then told the Review-Journal that he once supported a specific piece of legislation for the city in exchange for a pay raise and promotion. Unsurprisingly, the city could not turn a blind eye to what was essentially an admission of outright corruption, and ultimately terminated Williams a few days later.

But before his time with the city would officially end, Williams would participate in one last council meeting, where all parties — employer, employee and colleagues — acknowledged the problems and conflicts inherent to dual service.

Assemblyman and city employee Wendell Williams admitted that he used his power as a legislator to advance the interests of the government agency he worked for, rather than serving the public. A city councilwoman, meanwhile, acknowledged that governments sought to hire legislators because of the added “value” they provide as superlobbyists. Mayor Oscar Goodman explained that, to his understanding, the whole point of hiring a legislator on the city payroll was to ensure that “you have somebody up there who was looking out for the City’s best interest.”

Finally, the meeting revealed the challenges dual-serving legislators pose for the regular employee tasked with supervising them. When Williams’ direct supervisor was asked why she seemingly turned a blind eye to his misconduct, she offered an answer that rings true: she felt uncomfortable asking hard questions of her ostensible subordinate, given he also happened to be one of the state’s most powerful lawmakers.

The Williams scandal was so brazen that the council considered a policy prohibiting dual service going forward. But Las Vegas could not be the only one to play by the rules, Mayor Goodman explained. While the mayor acknowledged that the issue of dual service was admittedly “fraught with danger,” it nonetheless conferred a tremendous “advantage” for those agencies who engaged in it. Thus, to be the only agency to refrain from the practice would leave the city at a serious “disadvantage” when it came time to lobby the Legislature — and, quite understandably, the mayor did not “want to be at that disadvantage.”

Tyranny Defined: Prosecutor as Supreme Lawmaker

While few are as honest about the problems with dual service today as they were in 2003, the corrosive impact of dual-serving legislators has, if anything, only gotten worse.

Dual-serving legislators have in recent years consistently opposed efforts to improve transparency in government, while simultaneously voting to make information about the taxpayer-funded pensions paid to government employees (like themselves) hidden from public view.

Yet it is in the area of criminal justice, where government power is at its zenith, that the corrosive impact of dual service has been most pronounced.

Civil asset forfeiture is an abusive practice that allows law enforcement to seize the property of those who have never been charged, let alone convicted, of a crime. In 2019, Democrat Assemblyman Steve Yeager sought to fix this injustice by introducing Assembly Bill 420 — which would have restored basic due process protections to innocent property owners.

Unsurprisingly, the bill was supported by a massive, bipartisan coalition, and ultimately passed out of the Assembly by a 34-6 margin — with every Assembly Democrat and half of Assembly Republicans voting to make the bill law. AB420’s only meaningful opposition was the law enforcement lobby.

Unfortunately for innocent Nevadans, however, law enforcement had two incredibly powerful superlobbyists on their side — Senate Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro and Senator Melanie Scheible, both of whom are also Clark County prosecutors. The prosecutors/senators prevented AB420 from ever even receiving a vote in the Senate, thus ensuring its death.

At least 15 other Democrat-sponsored criminal justice reforms met the same fate in 2019, suggesting that while Democrats ostensibly controlled both houses of the Legislature, it was actually government — specifically the law enforcement lobby — that retained ultimate veto power.

Indeed, the naked influence of law enforcement was so obvious that even other Democrats criticized how broken the process had become. Then-Assemblyman Ozzie Fumo, for example, reportedly described the Legislature as “an oligarchy,” wherein Nevadans’ tax dollars went toward funding the “agenda” of law enforcement, rather than doing what “most people” wanted.

The practice of allowing those tasked with enforcing the law to also write the law — which has justly been described as the very definition of tyranny — continues to this day.

To wit, the decision as to whether to abolish the death penalty in Nevada currently depends on the approval of government itself — as represented by Clark County deputy district attorneys, and state senators, Nicole Cannizzaro and Melanie Scheible.

Government employees, including prosecutors, have every right to make sure their voice is heard before the Legislature, of course. Indeed, that is precisely what Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson did when he testified in support of maintaining the death penalty. The legislators considering his perspective, however, are supposed to be the people’s representatives, not fellow prosecutors.

Such absurdity is, however, what passes for “representative” government in Nevada today. Allowing those who wield the “awesome”[1] and “vast and unrestrained”[2] power of prosecution to also write the law is antithetical to a free society — which is precisely why the Nevada Constitution forbids it.

Yes, even the appearance of bias must be eliminated

Some may assert that dual-serving legislators can act in an unbiased manner, while ignoring the demands of their government employer. Even if such a noble person does exist, it is ultimately irrelevant to the reason for prohibiting dual service.

Given the lack of reliable mind-reading technology, proving actual bias is all but impossible, which is why institutions that rely on establishing trust in their fairness and impartiality, such as the legal system, seek to prevent even the “appearance” of potential bias. A doctor prescribing a certain medication shouldn’t be on the payroll of the company that manufactures that drug. Financial advisors shouldn’t work for the company whose stock they are pitching. And the people’s representatives shouldn’t be employed by the very governmental entities they are supposed to control.

In ruling that dual service violated their state’s separation of powers clause, the Oregon Supreme Court made this point eloquently:

“Our concern is not with what has been done but rather with what might be done, directly or indirectly, if one person is permitted to serve two different departments at the same time. The constitutional prohibition is designed to avoid the opportunities for abuse arising out of such dual service whether it exists or not.” Monaghan v. School District No. 1, Clackamas County, 315 P. 2d 797, 802-04 (Ore. 1957).

That ruling certainly proved prescient, given how dual-serving legislators like Wendell Williams took full advantage of the repeated “opportunities for abuse” that have plagued the Nevada Legislature for the past 70 years. And while Williams was an outlier in terms of his willingness to acknowledge it, it is absurd to think that others haven’t engaged in similar abuses, just because they may have been less vocal about it.

Dual service dilutes, if not destroys, the very foundation upon which the entire concept of representative government rests — that the Legislature reflects the will of the people, rather than government.

This explains why the Nevada Supreme Court previously described the separation of powers as “probably the most important single principle of government declaring and guaranteeing the liberties of the people.” The principle is so vital to a free society, the Court explained, that it must be applied with a “fullness of conception…involving all of the elements of its meaning and its correlations [in order to provide for] the maximum protection of the rights of the people.”

Indeed, “to permit even one seemingly harmless prohibited encroachment and adopt an indifferent attitude could lead to very destructive results.”

Those words were written in 1967. We’ve since seen admissions of outright corruption, with dual service described as a situation “fraught with danger,” that today functions as an “oligarchy” — and that’s just from those within this broken system.

In other words, the “very destructive results” that the Nevada Supreme Court once warned about are not mere hypotheticals — they have materialized. Now we just need to see if the Court still believes Nevadans are a free people who deserve to be protected from such abuses.