Solution of the Week: Collective Bargaining

Nevada’s first collective bargaining law, passed in 1965, expressly prohibited bargaining with government unions for all employee groups. It followed similar legislation passed six years earlier by North Carolina and stood in stark contrast to a concurrent wave of lawmaking across the states that gave union leaders representing government workers broad, coercive powers.

Union hostility toward Nevada’s law, however, prompted picketing by teacher union operatives on the Las Vegas Strip in a campaign designed to disrupt the state’s most important center of commerce. Acting at the behest of business leaders who wanted the disruptive picketing ended by any means necessary, Nevada lawmakers reversed the 1965 law during the 1969 legislative session. The new Local Government Employee-Management Relations Act required administrators within Nevada’s local governments to bargain collectively with unions representing all employee groups and to submit to a fact-finding mediation procedure to resolve impasses.

Subsequent legislation in 1977 created a binding arbitration procedure for police and fire unions that would guarantee union contracts. This power was extended to teacher unions in 1991.[1]

Key Points

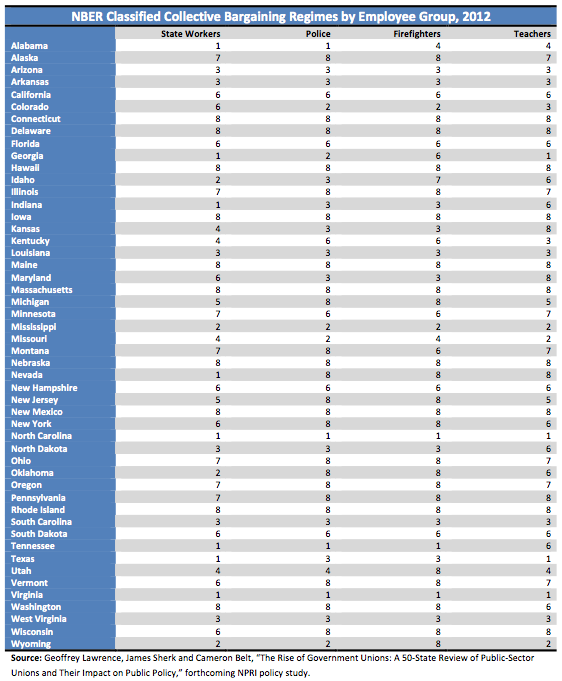

States can have one of several collective bargaining regimes. While the legal environment for collective bargaining in the government sector varies markedly by state, scholars with the National Bureau of Economic Research have classified state collective bargaining regimes according to the specific powers of compulsion given to union leaders. Ranked from the weakest to the strongest powers of compulsion, these are:

- Collective bargaining prohibited

- No legal provision for collective bargaining

- Collective bargaining permitted, but not required

- Public employers are required to “meet and confer” with union leaders

- Public employers have a duty to bargain collectively, express or implied

- Compulsory bargaining with fact-finding or mediation required

- Compulsory bargaining with strikes expressly permitted

- Compulsory bargaining with mandatory arbitration

The NBER coding scheme applies these rankings to each of five different employee groups: state workers, local teachers, local police, local firefighters, and other local employees. Thus, according to the NBER ranking system, Nevada’s laws grant the strongest possible powers to police, fire and teacher unions, while laws applying to other municipal workers have a rank of 6 and those for state workers a rank of 1.[2]

Econometric analysis shows that collective bargaining mandates adds tens of millions annually to Nevada’s cost of government. The NBER database, when updated, can be used to compare changes in collective bargaining laws to changes in state and local government spending, all across the country. This allows economists to illuminate the financial impact of a state’s choice in collective-bargaining regimes.[3]

Recommendations

Remove the powers of compulsion enjoyed by union leaders. Nevada lawmakers could realize tens of millions in annual cost savings by returning to the state’s original prohibition on government-sector collective bargaining. Nearly the same amount, however, is available just by ending the coercive powers held by union leaders to compel local governments to sign union contracts. With no provision, local administrators would be free to choose whether to bargain collectively based upon the wishes of constituents.

[1] R. Hal Smith, “Collective Bargaining in the Nevada Public Sector,” State & Local Government Review, Vol. 11, No. 3 (1979), pp. 95-98.

[2] Richard Freeman and Robert Valletta, “The Effects of Public Sector Labor Laws on Labor Market Institutions and Outcomes,” In When Public Sector Workers Unionize, 1988, pp. 81-106; Henry Farber, “Union Membership in the United States,” Working Paper #503, Princeton University, 2005.

[3] Geoffrey Lawrence, James Sherk and Cameron Belt, “The Rise of Government Unions,” Upcoming NPRI policy study.