PERS debt triples to $40B if consultant’s buried report is correct

While most financial experts are warning of future teacher shortages, decaying roads, higher taxes and cuts to public safety, members of the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Nevada (PERS) board are confident they can avoid all that by doing one simple thing: Produce investment returns higher than what even Warren Buffett expects to get!

Because PERS has failed to hit its investment targets over the past 5-, 10-, 15-, 20- and 25-year periods, government workers’ retirement costs have soared to today’s record-high 28 percent of pay (40.5 percent for police and fire officers) — which now consumes more than 12 percent of all Nevada state and local government tax revenue combined.

And as more money is sent to PERS, less is available for salaries, like the only $34,684 offered to new Clark County school teachers last year — almost certainly a driving factor behind the district’s perennial teacher shortages.

What’s worse, over 40 percent of what all government workers — excluding police and fire officers — pay towards PERS is spent on the system’s previously accrued debt, rather than on financing the employee’s future benefits.

Consequently, all new hires are expected to be net losers under PERS — receiving a benefit worth less than its total cost — which, unsurprisingly, will “negatively affect current teacher quality and retention,” according to scholars at the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Retirement costs for police and fire officers are even higher: Paying PERS an amount equal to 40.5 percent of their salary means fewer cops on the street.

The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, for example, has sat on roughly $100 million in funds explicitly designated for hiring new cops for over a decade now — likely anticipating the future explosion in retirement costs to come. In fact, despite the surplus, Metro is pushing for yet another tax hike, citing their ever-increasing personnel costs.

But that was just the tip of the iceberg.

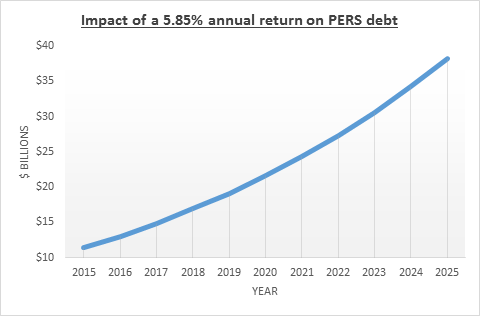

PERS debt is projected to explode over the next decade, rising from roughly $11.4 billion to over $38 billion if the average 5.85 percent annual investment return forecast of the consultant hired by PERS — Wilshire Associates — is accurate:

To put that in perspective, in 2013 Nevada spent less than $3 billion on police, highways and fire protection combined.

Servicing a debt of this size would require similarly massive increases in contribution rates, inevitably requiring lower wages for government workers, cuts to vital services and higher taxes.

At that point, it’s likely that there would simply not be enough taxes to hike and services to cut to make PERS solvent — leaving no other choice but to cut the benefits promised to retirees.

In order to avoid that fate, and save PERS, Nevada lawmakers must act with the urgency that this situation demands.

How we got here

PERS is different from retirement accounts in the private sector, where workers’ contributions are deposited directly into individually owned accounts.

In PERS, workers’ retirement contributions are all pooled together in one large fund, with members promised a fixed future benefit based on salary and work experience — similar to how Social Security works.

Consequently, PERS must make a series of projections to determine how much workers must contribute in order to ensure their promised, future benefit is fully funded. One of the most significant projections PERS makes is its assumed 8 percent annual investment return.

In other words, PERS would consider a $10 payment due in 30 years as fully funded with only $1 today — as the expected gains from investing that $1 would bridge that $9 gap over time.

Unfortunately, if PERS investments underperform that target, taxpayers and government workers must bail them out via higher contribution rates.

But using expected investment returns to discount guaranteed future benefits amounts to serious malpractice, which is why such an approach is rejected by private U.S. pension plans, public and private plans in Canada and Europe, and 98 percent of financial economists. U.S. public pension plans are the only dissenters from this consensus.

The easiest way to see why this is wrong is to look at what happens by raising that rate. Imagine the Governor and the Legislature uniformly demanded the PERS board must immediately pay down the approximately $11 billion unfunded liability it currently reports.

Sounds like an impossible task, right?

But because of the flawed PERS accounting methodology, the board could appear to pay off that entire amount in an instant. All that would be needed is for the PERS investment advisor to claim that instead of an 8 percent annual return, he now believes PERS can return 10.5 percent.

Presto! PERS would have eliminated their entire $11 billion debt, and would actually enjoy a slight surplus to boot!

Of course, their actual unfunded liability — over $50 billion using correct accounting — hasn’t changed.

If that approach sounds fishy to you, you’re in good company. This topic is addressed in more detail in Appendix B.

But given that this is the approach PERS board members employ, they should be extremely vigilant in ensuring their assumed investment return is one that they can confidently expect to hit.

Instead, they ignore both their poor past performance, as well as the projections of their own, hand-picked consultants who are warning that the board’s assumed annual rate of return is far too high.

After a careful selection process, PERS last year commissioned a second-opinion review by Wilshire Associates, which, on August 20, 2015 informed the Board that it was most likely to realize only an average annual return of 5.85 percent over the next decade — not the 8 percent minimum PERS must hit to avoid falling further into debt.

Wilshire’s assessment of lower expected future returns is shared by virtually all major industry experts.

The McKinsey Global Institute, for example, warned that, “After an era of stellar performance, investment returns are likely to come back down to earth over the next 20 years.” Based on McKinsey’s projections, PERS can expect a 20-year return ranging from as low as 4.6 percent under a “slow-growth” recovery to as high as 7.4 percent under a “growth-recovery” scenario.

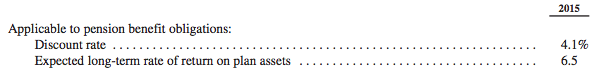

Even investing guru Warren Buffett uses a mere 6.5 percent assumed long-term rate of return for Berkshire Hathaway’s pension plan.

Because of this, most U.S. public pension plans are now lowering their investment targets. For example, the nation’s largest public pension plan — CalPERS — implemented a plan last year to gradually drop their 7.5 target to 6.5 percent over the next several years.

A broken governance structure

So why does PERS — in defiance of its peers, experts and its own consultants — continue to employ an 8 percent assumed rate of return?

Political self-interest.

After PERS investment advisor Ken Lambert offered a few half-hearted reasons to justify dismissing the Wilshire report — which are addressed in Appendix A — the Board asked for a precise calculation of what lowering its rate to 7 percent would entail.

Such a move would increase the non-safety contribution rate from 28 to 38 percent of pay, at which point, according to Lambert, “We’ll all go home” — apparently predicting massive rebellion by public employees that would drive the current board and its staff out of office.

PERS here illustrates the core error built into the governance structure of U.S. public pension plans: Short-term board members, with no skin in the game, face a set of incentives where they are actually punished for doing the right thing, and benefit from pushing costs off onto future generations.

Given that understanding, it’s easy to see why PERS characterized the Wilshire report as meriting “no rush, no real urgency” and containing “nothing [that] is actionable,” when Nevada State Education Association president Ruben Murillo repeatedly, and correctly, pressed the board for answers.

PERS now finds itself in a Catch-22 situation: Because board members have for so long failed to face reality, costs will skyrocket if they should now adopt correct assumptions. Yet, failing to do so will only further compound their initial mistake — and the resultant carnage — when the day of reckoning finally arrives.

Significantly, because PERS only has about 72 cents of every dollar of promised benefits on hand, the system actually needs to outperform its 8 percent investment target. Only then would the system have enough money to make good on its promises.

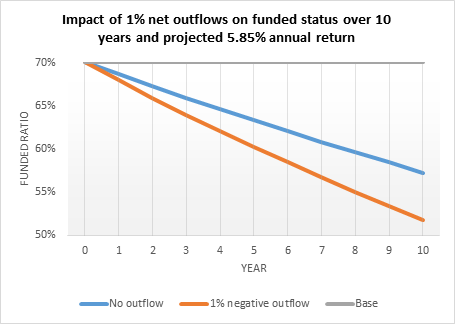

Making matters worse is the fact that PERS is now cash-flow negative — paying out more in benefits than it collects in taxpayer and employee contributions.

If this trend persists and Wilshire’s projected investment returns are realized, PERS could easily find itself approaching a funded ratio of only 50 percent — which is considered a “crisis-point” that is “very difficult to climb out of,” by CalPERS Chief Investment Officer Ted Eliopoulos.

Even though the call for reform enjoys widespread, bipartisan support and includes at least one former PERS board member, Warren Buffett’s assessment of public pensions still rings sadly true in Nevada:

There probably is more managerial ignorance on pension costs than any other cost item of remotely similar magnitude. And, as will become so expensively clear to citizens in future decades, there has been even greater electorate ignorance of governmental pension costs.

Thankfully, there is still time left to save PERS, but it will require immediate action by the Nevada Legislature.

The most responsible reform would be legislation similar to the model embraced by Arizona last year, which was so beneficial to all stakeholders that even the police and fire unions supported it.

The particulars of reform are much less important than acknowledging the fundamental problems. As officials with Oregon’s pension plan stated of their similar crisis: “This is becoming a moral issue. We can’t just talk about numbers anymore.”

Robert Fellner is the director of transparency for the Nevada Policy Research Institute, a nonpartisan, free-market think tank. To learn more about PERS visit www.npri.org/issues/detail/pers.

Appendix A: A fundamental misunderstanding of how pension funding works

PERS investment philosophy can best be described in the words of the system’s former chief investment officer and now hired consultant. Said Ken Lambert, responding to the Wilshire report, “My answer to this discussion is: Why did you waste that air? Because I don’t care. Because I have 30 years, I don’t have [merely] 10 years.”

The view that pension funds only need to concern themselves with long-term investment averages is simply incorrect for at least two reasons, according to the experts at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government.

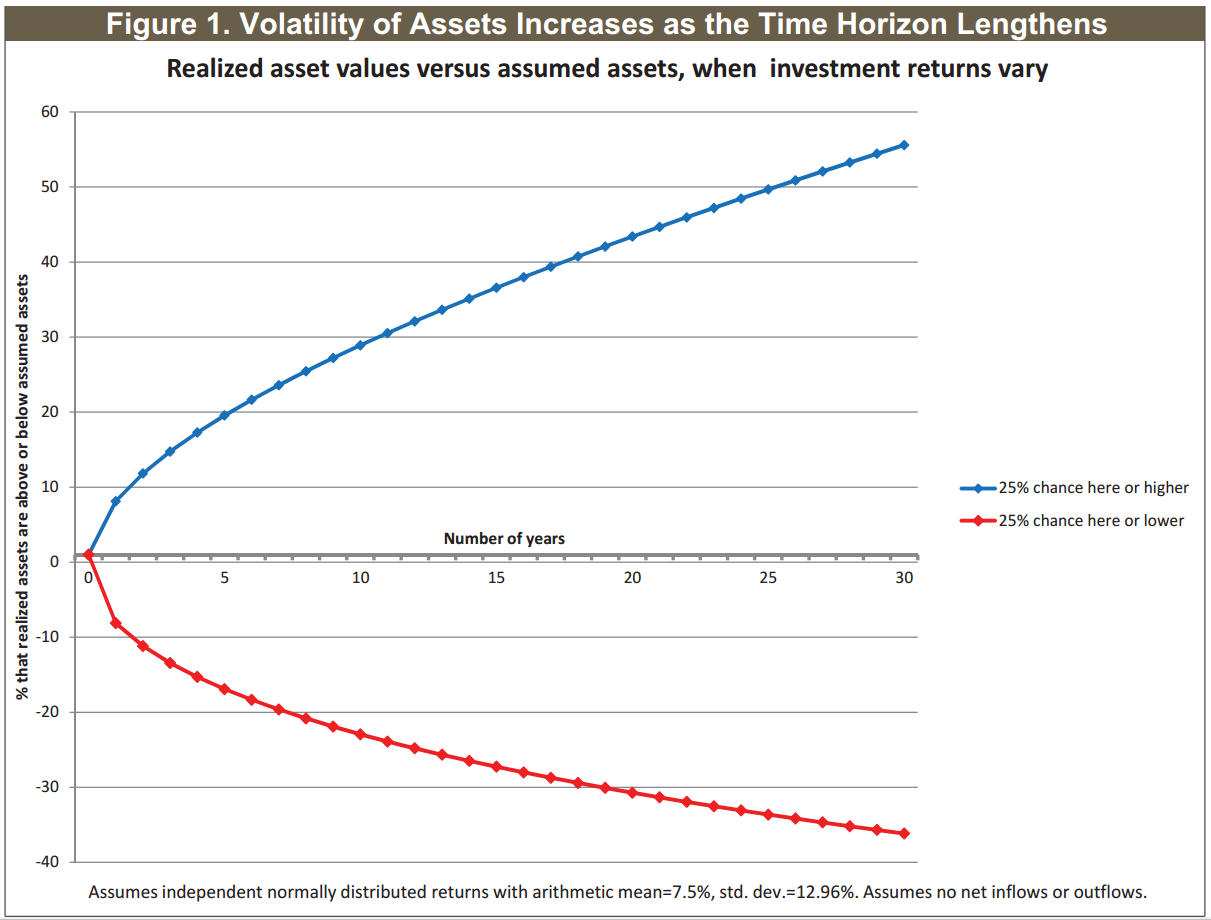

Reason #1: A tremendously wide range of possibilities exist over a 30- and even a 50-year time frame.

Analyzing the probability of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) hitting its 7.5 percent investment target, the Rockefeller Institute found that:

Even if we extend the horizon to fifty years, there’s a 68 percent chance that return would fall between 5.7 and 9.3 percent — and a 32 percent chance that average returns will fall outside that range. Simply put, there is no reason to expect that pension funds will actually ‘get’ their assumed rates of return, just as a gambler’s chance of recouping accumulated losses worsen over time.

While the specific numbers would change slightly, the overall findings are equally applicable to PERS, which has made a promise to pay retirees 100 percent of the time, not just when the system finds itself on the right side of investment variance.

Reason #2: The risk that pension funds will not be able to pay benefits does not diminish with time; it increases.

Two separate studies by the Rockefeller Institute make this point:

Public Pension Funding Practices: “Although pension funds are long-term investors, the risk of severe underfunding actually increases with longer investment horizons — the range for expected investment returns narrows with time, but smaller differences are compounded over more years.” (Emphasis added.)

And

Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans: “…because differences between expected return and actual returns accumulate and compound as the time horizon extends, pension fund assets actually become more volatile with time, not less.” (Emphasis in the original.)

In other words, while the fund is more likely to hit its average rate of return over an extended time period, the damage done from periods of underperformance is amplified by each successive year.

Ultimately, what PERS members care about is whether the fund will have enough assets on hand — not a statistical average of investment returns.

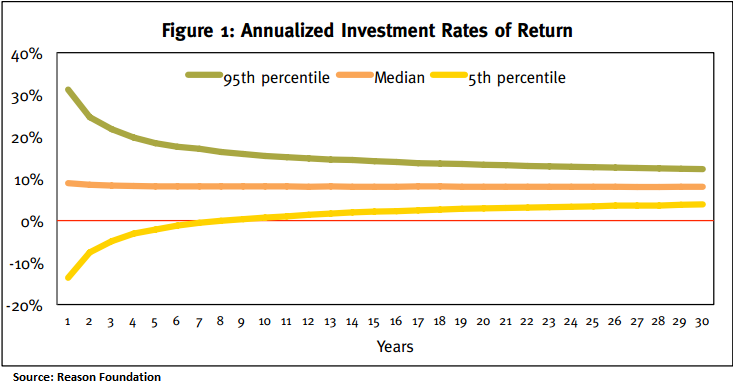

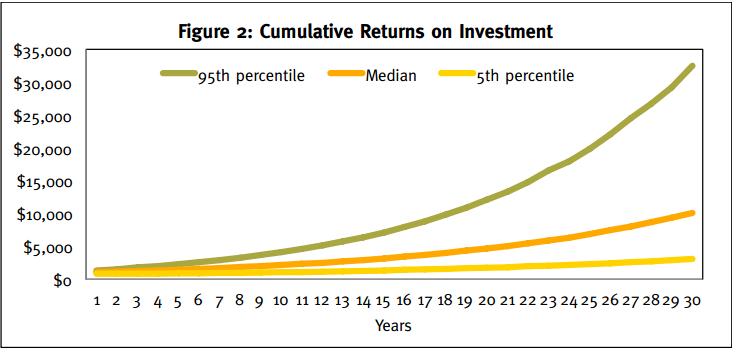

Experts at the Reason Foundation put together a pair of graphs that illustrate this concept beautifully. Figure 1 shows the narrowing of annualized rates of return, while figure 2 shows the actual dollar amount of returns:

This point is even more critical given that PERS is roughly 72 percent funded today. So even if PERS were able to produce an 8 percent average annual return over the next 30 years, it still won’t be enough, as those later years of (presumably) above-average returns would be applied to a lower-than-needed asset base.

The Rockefeller Institute scholars leave no margin for error on this issue:

Some have argued that pension funds are long-term investors and can count on investment risks evening out over the long run. This is simply incorrect and is a myth often put forth uncritically in public pension debates. While the long-run volatility of investment returns does diminish with time, because returns are compounded over time the risk of asset shortfalls actually increases the longer the duration, and assets are what funds must use to pay benefits…The risk that pension funds will not be able to pay benefits does not diminish with time; it increases. Governments can’t simply ride out the fluctuations in the belief that good returns will balance bad.

Cash-flow negative

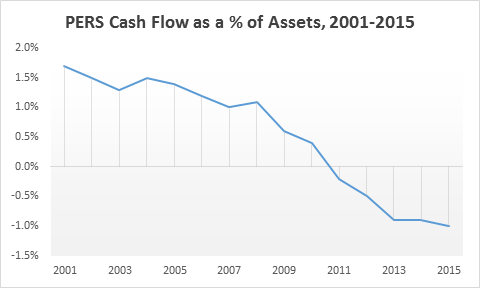

But PERS situation is even worse than that, as the system is now cash-flow negative for the first time in history: Last year, the amount PERS paid out in benefits exceeded total contributions by an amount equal to 1 percent of the total fund size. Remarkably, Ken Lambert appeared to totally dismiss this serious financial event, referring to it to as only a “rounding error” — seemingly oblivious to the precarious context in which the event has occurred. As the below chart reveals, this is a developing trend that is likely to get worse in coming years as more PERS members become retirement eligible.

Just as PERS was wrong to dismiss the findings of the Wilshire report, dismissing the impact of becoming cash-flow negative is a grievous mistake as well.

Let’s illustrate the effect of that rounding error, remembering that a 7 percent annual investment return instead of 8 percent would require at least a 10 percentage point increase in contributions.

Effect of PERS negative outflows at 1% of fund size

|

Outflow |

Starting fund size |

Fund after inflows/outflows |

Fund size after an 8% investment return |

|

None |

$100 |

$100 |

$108 |

|

-1% |

$100 |

$99 |

$106.92 |

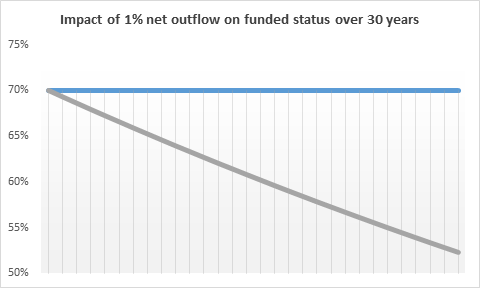

As a result of just a 1 percent net outflow, even if PERS hits its 8 percent target the fund will grow only by 6.92 percent.

Said differently, whatever amount a fund is cash-flow negative consumes that much of any year’s annual return. So being 1 percent cash-flow negative turns an 8 percent return into only 7, and would require an investment return of just over 9 percent to increase the fund enough to sufficiently offset that year’s growth in liabilities.

The below chart shows the impact of a 1 percent negative outflow versus being cash-flow neutral, even if PERS returned 8 percent every year:

The next chart shows the projected decline in funded status that would occur if PERS investment returns matched Wilshire’s forecast with and without a 1 percent net outflow each year:

Appendix B: What is a discount rate?

“While economists are famous for disagreeing with each other on virtually every other conceivable issue, when it comes to this one there is no professional disagreement: The only appropriate way to calculate the present value of a very low-risk liability is to use a very-low-risk discount rate.”

— Donald Kohn, former Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.

The only reason the PERS investment target attracts so much focus is because the PERS board also uses that value as the system’s discount rate, a practice rejected by everyone outside of the U.S. public pension industry.

So what is a discount rate?

Imagine the IRS showed up on your door with a notice that you owed them $100 and failure to pay would result in immediate imprisonment. But now imagine there are two choices for the due date of this bill: immediate or 10 years from now. Obviously, we would all choose the latter. The financial value conferred by having so much more time to pay that liability is reflected through the use of a discount rate.

So, if the above example applied to a corporation and not an individual, a $100 liability due immediately would be reported as $100, while one not due for another 10 years would be much smaller. How much smaller all depends on the discount rate used. That rate should reflect the likelihood that the payment would be made. For most of us, the IRS bill would be a payment that we would make with 100 percent certainty, so the discount rate must reflect that probability.

Another way to think of it is what is the least amount of money you would be comfortable setting aside today to fund that $100 bill due in 10 years?

If the US government offered a 10-year Treasury that paid 2.5 percent annual interest, one could invest only $78 and be guaranteed to receive $100 by the time the bill was due. By using that guaranteed rate of return (also known as the “time-value of money”) as the discount rate for our liability, the present value of our $100 tax bill due in 10 years would be discounted to only $78 today. In financial terms, that $22 reduction in the $100 we owe reflects the value of having 10 years to make good on that payment.

PERS, however, violates this basic rule of finance by discounting the cost of guaranteed benefits by using an assumed average investment return.

Consequently, in the example above, PERS would report a debt of $100 due in 10 years as a $46 liability, not the $78 used by all financial economists.

But notice that the total amount owed — $100 — hasn’t actually changed, only the reported liability did. This is why the use of inappropriately high discount rates is so destructive: It hides the true size of PERS liabilities from public view. Even worse, the only time that publicly reported liabilities rise to reflect their true size is after a period of poor investment returns, precisely when it is too late to do anything about it!

Let’s illustrate this concept by comparing how PERS and Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway would treat the same $100 liability due 20 years from now. Below is the information used by Buffett’s pension plan:

The most obvious difference is that the discount rate and investment returns are treated separately. This demonstrates that correctly using a liability-based discount rate does not mean a fund must invest in only low-risk securities.

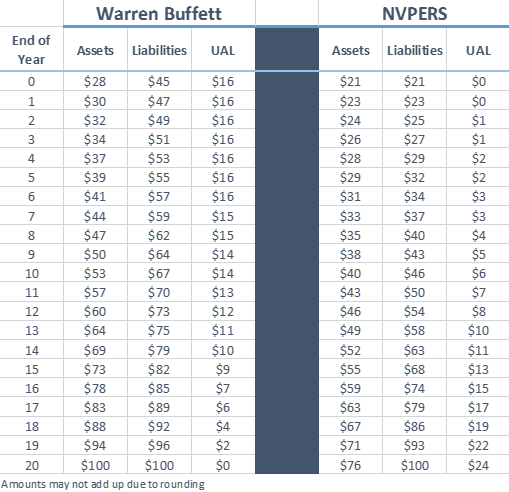

Now let’s examine the differences between the Buffett and the PERS approach. The below chart assumes Buffett’s investment expectations are accurate, and that both he and PERS experience 6.5 percent annual investment growth. The UAL column reports the resultant unfunded actuarial liability.

How Berkshire Hathaway and PERS value the same $100 liability due in 20 years

The most immediate difference is the size of the liability initially reported. Berkshire’s shareholders are presented with a more accurate depiction of the size of its outstanding liabilities — which it reports as more than twice what PERS reports the exact same obligation.

Secondly, Berkshire’s approach more accurately reflects the uncertainty of investment returns, which only shrinks the UAL as they are realized.

PERS, however, uses the exact opposite approach. By treating assumed returns as certain, the true size of its liabilities are hidden until after investment returns underperform.

Berkshire’s approach means that a plan can be comfortably funded as long as it is above 80 percent — as assets are expected to grow faster than liabilities.

But when a fund uses the same value for its discount rate and assumed investment return, anything less than 100 percent funded is unsafe — as the assumed growth in assets is offset by an equal growth in liabilities, preventing the fund from becoming solvent.

Why hasn’t this come up before?

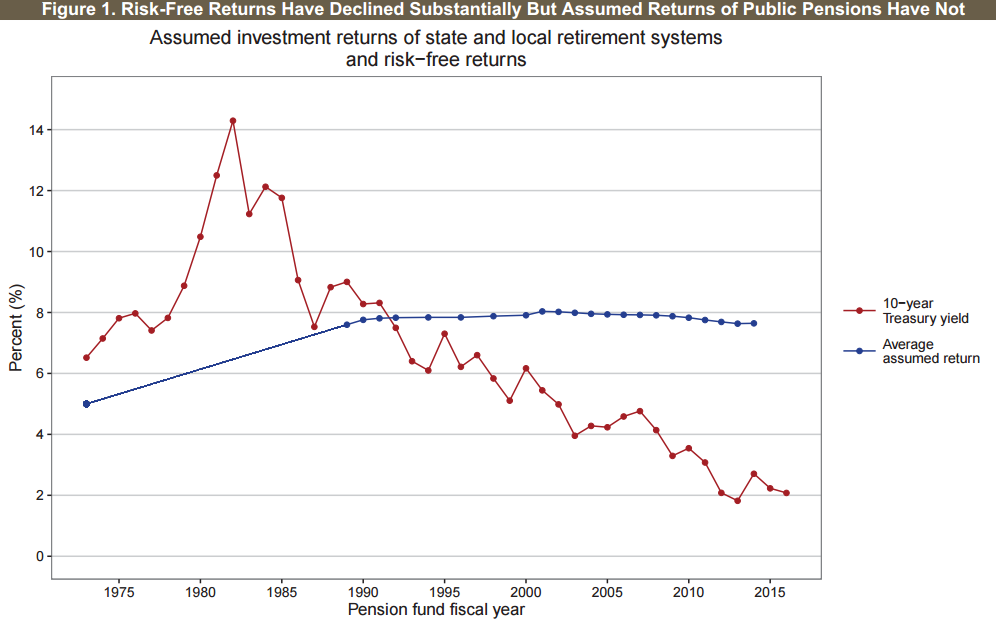

While PERS was always technically incorrect to use a discount rate based on assumed investment returns, historically it didn’t matter much when Treasuries were yielding 8 percent and, consequently, 8 percent was the appropriate discount rate at that time.

Source: Rockefeller Institute of Government, State University of New York

Yet, now that Treasuries are yielding around 2 percent, the continued use of a discount rate of 8 percent is wildly inappropriate — as it far surpasses the current time-value of money.

This also destroys the claim that using an 8 percent discount rate today is acceptable because PERS currently boasts a 9.2 percent annualized return from 1984-present — as it was essentially impossible to return less than 8 percent from 1984-1995 given the yield on Treasuries during that same time period.

Further reading:

- Healthy Pension Fund Governance, Stanford lecturer David Crane

- Strengthening the Security of Public Sector Defined Benefit Plans, the Rockefeller Institute

- Best Practices for Setting Public Sector Pension Fund Discount Rates, the Reason Foundation