New Data Shows Behavior Remains Primary Determinant of Income

Defeatism seems to have gripped American society of late. A Gallup survey last fall showed that only 42 percent of Americans now believe the next generation will enjoy a greater standard of living than their own – an 18-point decline from 2019, prior to the pandemic.

Other polls show core American values have changed substantially since the pandemic. A Wall Street Journal poll in August 2019 revealed 89 percent of Americans thought hard work was very important and 62 percent believed community involvement was very important.

A subsequent Wall Street Journal poll conducted in March 2023 showed the proportion of Americans holding these values had fallen to 67 percent and 27 percent, respectively.

Enthusiasm for having children also fell from 43 percent to 30 percent. Fewer Americans even consider tolerance for others a top priority in 2023, with 58 percent saying that value is very important versus 80 percent in 2019.

These are seismic changes in public attitudes over a mere three-and-a-half years. What undergirds this creeping malaise?

There are many factors, to be sure. Fortune Magazine author Molly Barth bemoans pervasive despair and “financial nihilism” among young Generation Z, saying “From graduating during a global pandemic to current fears around wage stagnation, growing inequality, and an impending recession, many feel that the cards are stacked against them.”

But one narrative that has captured attention recently is a claim that hard work no longer pays. As Yale historian of labor unions Jennifer Klein recently told Business Insider, “the payoffs of hard work have been insecurity.”

A deluge of new government spending since 2020, financed primarily by money printing, has devalued the currency and wreaked havoc on household finances and is clearly a cause for concern among Americans of all ages.

But the notion that work no longer pays is a claim that can be easily tested.

Last month, the Census Bureau released data on the household income distribution in 2022 and those numbers reveal that very little has changed in terms of the behaviors that leads to above-average incomes.

As I wrote a decade ago, the primary determinant of a household’s position on the income scale is still the decision to work.

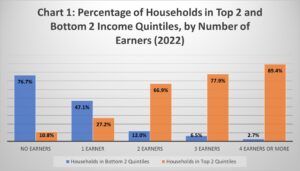

Unsurprisingly, more than three-quarters of households with no income earners fell in the lower income classes.

However, nearly half of households with a single earner also fell in the bottom two income quintiles.

Households with two or more earners, however, fall overwhelmingly in the top two income quintiles. Nearly two-thirds of households in the top income quintile had four or more earners and almost 90 percent of four-earner households were in the top two quintiles, as Chart 1 shows.

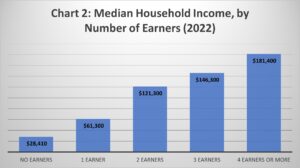

Another way of looking at this is to compare the median incomes of households by number of earners.

Chart 2 does this and shows a direct correlation between the number of earners and household income.

These trends haven’t changed much over time and indicate, as one might guess, that the amount income-generating employment is the primary determinant of a household’s position on the income distribution.

There are other interesting insights to be gleaned from the data, all of which remain consistent with past experience.

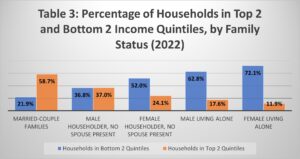

For instance, households headed by married couples are far more likely to be in the top two income quintiles than any other group.

Table 3 shows nearly 60 percent of these households were in the top two quintiles while slightly more than one in five were in the bottom two quintiles.

By contrast, households of both males and females living alone had the most prevalence among the bottom two income quintiles, with nearly three in four females living alone found in those categories.

Interestingly, having children appears to motivate higher incomes even for single parents, as these households fare much better than adults living alone.

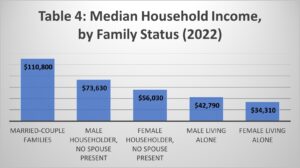

Table 4 displays the median household incomes by family status, which further illustrates that being married and having children is positively associated with higher incomes.

These phenomena are partially explained, of course, by a head of household’s age.

Young adults tend to live alone and occupy entry-level or junior positions at work, so their income is lower than a middle-aged person who has progressed along their career path and is more likely to have found a spouse or have children.

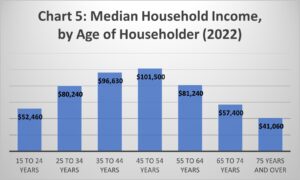

Table 5 shows the median household income by age of the head of household, which confirms prior expectations that individuals achieve peak earning potential in their 40s and 50s after having accumulated years of professional experience and prior to entering retirement years.

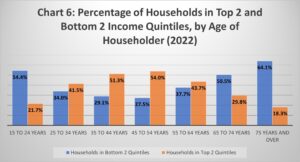

Likewise, Chart 6 shows that heads of household in the youngest age bracket – those holding entry-level jobs – and in the oldest age brackets – those no longer working – are the only groups more likely to fall in the bottom two income quintiles than in the top income quintiles.

Households headed by individuals aged 45 to 54 are roughly twice as likely to be in the top income classes than in the bottom income classes.

Other factors that matter primarily center around the location of the household.

Better employment opportunities are available in some locales than others. This applies to both the region of the country as well as urbanicity.

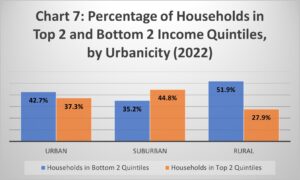

Chart 7 shows that rural households are nearly twice as likely to fall in the bottom two income quintiles than the top two quintiles.

Better income opportunities exist in metropolitan areas, but as individuals age, get married and have children, they tend to relocate to suburban neighborhoods within these metropolitan areas.

So, suburban households – strongly correlated with age and family status – are more likely to fall in the top income classes than the bottom classes.

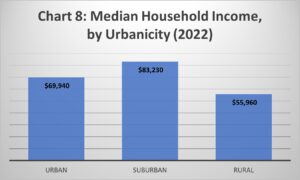

Chart 8 illustrates the same trends by examining the median household income of each group. The median urban household earns 25 percent more than the median rural household.

Meanwhile, the median suburban household earns 19 percent more than the median urban household.

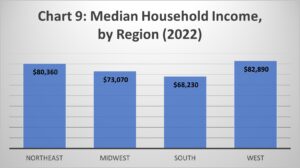

Finally, income tends to be more lucrative in the Northeast and West regions of the United States in comparison with the Midwest and South.

Western households earn the highest median income, as seen in Chart 9, and these households earn 21.5 percent more than the median household in the Southern U.S., which has the lowest incomes.

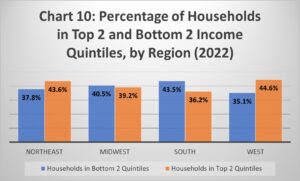

Chart 10 also shows that only Southern households are significantly more likely to fall in the bottom two income classes than in the top two, while Midwestern households are roughly even.

This information shows that the behaviors and other factors that determine a household’s income status remain consistent with previous expectations.

Contrary to some claims, the core of the American economic system has not fundamentally changed or broken.

Rather, to the extent malaise or “financial nihilism” have taken hold, the cause appears to rest primarily with macroeconomic factors such as inflation and tight capital markets as government spending increasingly crowds out private-sector investment and devalues the currency.

These factors are causes for frustration, to be sure, but they can be reversed over the medium term through change in policy.