A Zero-Risk Society is Not a Reasonable Policy Proposal

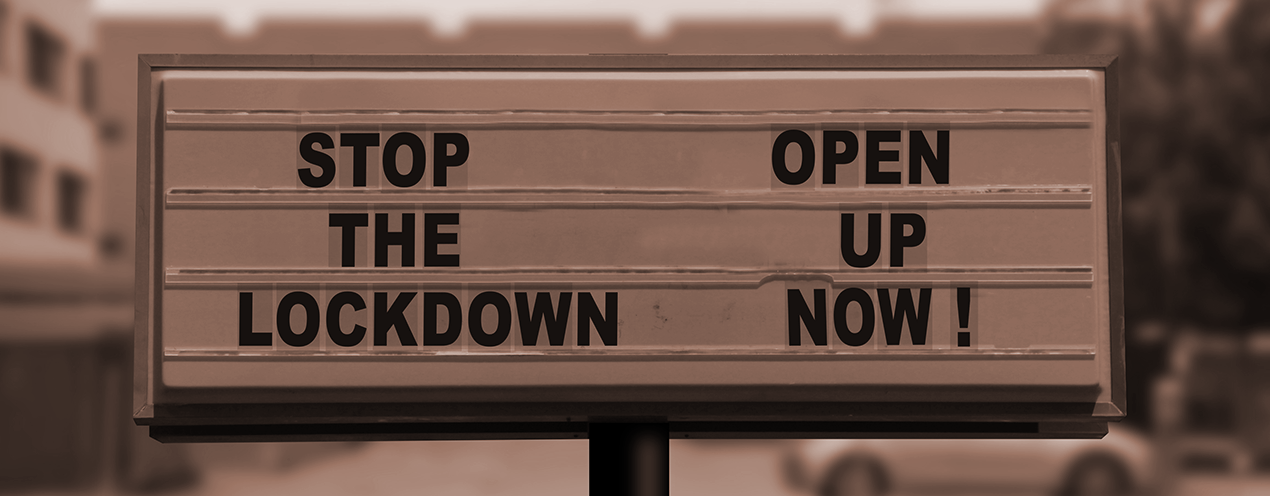

Some Nevadans might be old enough to remember when “two weeks to slow the spread” was the official position of most governors invoking vast emergency powers in response to the novel coronavirus. Long gone are those days.

For more than a year, we have lived in a world where one-man-rule suddenly usurped representative democracy as the standard form of state government and where the policy goals of these newly empowered authoritarians have been ever-evolving. What began as a suspension of democratic norms to save our healthcare infrastructure from being overwhelmed during a global pandemic, has creeped into arbitrary regulatory attempts to micromanage away even the most trivial risk of contagion.

With vaccines to the novel coronavirus now being widely distributed one might think the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would be in celebratory mode. Instead, the agency has been patronizingly warning Americans that even vaccination won’t excuse a return to pre-pandemic normalcy—arguing that social distancing, mask mandates and other precautions should continue to be observed into the foreseeable future.

In pre-pandemic times, such CDC guidance would have been greeted by Americans with the same ambivalence and apathy shown toward the agency’s risk-intolerant guidance on more mundane parts of life—such as the agency’s contempt-laden recommendations on limiting alcohol consumption.

However, this is the era of COVID, and as such the CDC’s recommendations are being regularly transformed into public policy by governors eager to demonstrate to constituents that they are “doing something” to reduce the risks posed by a global virus.

The problem, however, is that mitigating risk doesn’t come without costs. After all, a single digit speed limit would, undoubtedly, help reduce the risk of death from traffic accidents—however, the social cost imposed on commuters would be simply intolerable for most Americans. As the CDC suggests, moving toward an alcohol-free lifestyle is the only certain way to reduce the health risks associated with alcohol consumption—yet few Americans would tolerate a return to the days of prohibition.

Throughout most of our lives, we understand that risk exists all around us, and we mitigate it by balancing our individual concern for safety with that of our lifestyle and countless other social and professional considerations.

With a growing number of states starting to reject the impracticality of keeping their economy in a perpetual state of pause, nannystate cheerleaders are falling over themselves to decry the “irresponsibility” of allowing citizens to once again manage their own lives. However, states like Georgia, Florida and Texas aren’t plunging their citizens into an apocalyptic future by drastically reducing coronavirus regulations—they’re merely returning to individuals the ability to manage their own exposure to risk.

After all, Texas isn’t forcing citizens to crowd into busy bars or leave their masks at home. Most businesses, in fact, will continue to take precautions against viral transmission and require patrons to behave accordingly—and many citizens will continue to socially distance, wash their hands and wear masks when it is appropriate to do so. And that’s the point: In states that are opening up, the decisions about how best to mitigate risk will—once again—belong to individuals rather than politicians wielding the heavy (and destructive) power of government coercion.

Unfortunately, governors and elected officials—desperate to be seen as doing “something” in a time of uncertainty and chaos—have convinced many Americans that outsourcing such personal responsibility to the political class is somehow necessary.

The result has been a never-ending parade of regulations, restrictions and limitations on the social and professional lives of Americans. And while “the spread” has long since been slowed, governors nonetheless continue to cling to (and, in some cases, even expand) the unprecedented powers they assumed for themselves more than a year ago, as a way to wage war on the risks (real and imagined) associated with coronavirus.

As long as citizens agree to continue outsourcing such intimately personal and individual responsibilities to the political class, last year’s perpetual state of emergency powers and undemocratic authoritarianism—just like concerns about coronavirus itself—will never actually go away.

This article was originally published at Nevada Business Magazine